Like the proverbial pink elephant in the room, one assumes that a ship is immediately and obviously identifiable. However, locally, and internationally, the definition of what is a ship has proved illusory, the criterion being “at sea” as it were.

Among the more unusual cases which have come up for determination would rank the following:

- Houseboats & floatels i.e. floating motels (The Environment Agency v Gibbs and another [2016] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 69, Addison v. Denholm Ship Management (UK) Ltd. [1997] I.C.R. 770);

- Flying boats (Polpen Shipping Co.v Commercial Union Assurance Co., Ltd (1942) 74 LI LR 157); and

- A remotely operated underwater vehicle (Guardian Offshore AU Pty Ltd v Saab Seaeye Leopard 1702 Remotely Operated Vehicle Lately on Board the Ship “Offshore Guardian” and another [2020] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 201).

To add to the list of curious cases, in the landmark case of Vallianz Shipbuilding & Engineering Pte Ltd v Owner of the vessel “ECO SPARK” [2023] SGHC 353 (“EcoSpark”), the Singapore Court had occasion to consider whether or not a floating fish farm (a modern day kelong in local parlance), was a ship for purposes of the HCAJA. In so doing, the Singapore Court has attempted to put forward a more comprehensive rubric by which to determine what is a ship, and this article wades into these murky waters by way of a case review.

The High Court (Admiralty Jurisdiction) Act 1961 (2020 Rev Ed) (“HCAJA”) is the legislation that sets out the ambit of the local Courts’ admiralty jurisdiction. Section 2 of the HCAJA defines “ship” as simply “any description of vessel used in navigation”. However, a neat definition of a “ship” or “vessel” has proved elusive. The High Court in EcoSpark has held (at [69]) that of necessity, the inquiry as to what constitutes a “ship” must be multi-factorial.

Practically speaking, the more ship-like characteristics one could tick off, the more likely the vessel is a “ship” and vice versa. However, the absence of certain characteristics does not immediately mean that the vessel is not a “ship”.

Relevant physical characteristics

Insofar as physical characteristics of a vessel were concerned, the “ability to self-propel, being possessed of a keel or a steering mechanism such a rudder, having a crew to man the ship, navigation lights, and ballast tanks” are usual physical characteristics (at [73]) and a vessel having all or most of these characteristics is more like than not to be a “ship”.

Design and capability of being used in navigation

At its very essence however, the Court noted that whether a vessel was “designed and capable of being used in navigation” was a weighty consideration in determining whether or not a vessel was a “ship” within the meaning of the HCAJA.

In that regard, a vessel must be designed to be capable of movement from one place to another on the water, but, need not be currently used to move from one place to another on water. Inasmuch as a car parked in a parking lot remains a car, a vessel not currently traversing the water (but capable of it) remains a vessel.

In addition, the Court declined to follow the line of authorities which hold that the vessel’s primary work should be executed while in navigation, and adopted instead the reasoning in the English Court of Appeal in Perks v Clark (Inspector of Taxes) [2001] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 431, that navigation can be incidental to another function such as dredging or providing accommodation.

Class and flag

Further to the above, the classification of the vessel, and registration and flag of the vessel in question has also been flagged out an important indication as to whether the vessel is a “ship” and/or “used in navigation”.

Conclusion

In this case, notwithstanding that the vessel the ECO SPARK, lacked many of the usual physical characteristics of a ship e.g. no engines, no crew, no navigational equipment, the Court noted that the vessel, being a converted dumb barge, was designed for and remained capable of being in navigation. The fact that she had special structures installed on top of the barge structure did not render her no longer navigable.

While the vessel was spudded down into the seabed and does not move on a daily basis, she is capable of being moved and remains capable of navigation. In addition, the fact that she had been towed from Batam to Singapore immediately prior to her use as a floating fish farm, and her capability of being classed (notwithstanding that her owners had not maintained her class status), pointed to her being a ship for the purposes of section 2 of the HCAJA.

In conclusion, this judgment is a timely and illuminative one and provides a greater degree of certainty and clarity as to when the admiralty jurisdiction of the Singapore courts is to be invoked.

Some of the more common offences a driver may face under the Road Traffic Act 1961 (the “RTA”) include “Reckless or dangerous driving” under Section 64 of the RTA (“Reckless Driving”) and “Driving without due care or reasonable consideration” under Section 65 of the RTA (“Careless Driving”). This article explores what these offences mean and the judicial approach to dealing with such offences, as well as some of the possible outcomes a person may face when charged with such offences.

Defining the Offences

First, when faced with a possible RTA offence, it is important to understand whether one’s conduct amounts to “carelessness” as opposed to “recklessness” which is more severe. These terms are not defined in the RTA but have developed over case law.

Broadly, recklessness involves the offender’s recognition of a risk (such as beating a red light, or driving under the influence) but ignoring that risk. Recklessness can also be made out where a risk is obvious but the driver unreasonably failed to consider it. Carelessness on the other hand is typically made out when a driver’s actions fall below what is reasonably expected of a competent driver.

Second, there are 4 degrees of harm involved in such offences: death, grievous hurt, hurt, and non-injury scenarios or property-damage-only cases.

“Hurt” is elevated to “grievous hurt” when among other things, a victim has suffered permanent blindness or hearing loss in either eye, amputation, permanent disfiguration of the head or face, permanent incapacity to a body part, a fracture or dislocation of a bone (including the cartilage in the nose) or has been placed on medical leave for 20 days or more. The full list may be found at Section 320 of the Penal Code 1871.

The dividing line between what is reckless and what is careless is not always clear but this line must be drawn as the fines and / or imprisonment terms imposed can differ significantly between Reckless and Careless Driving.

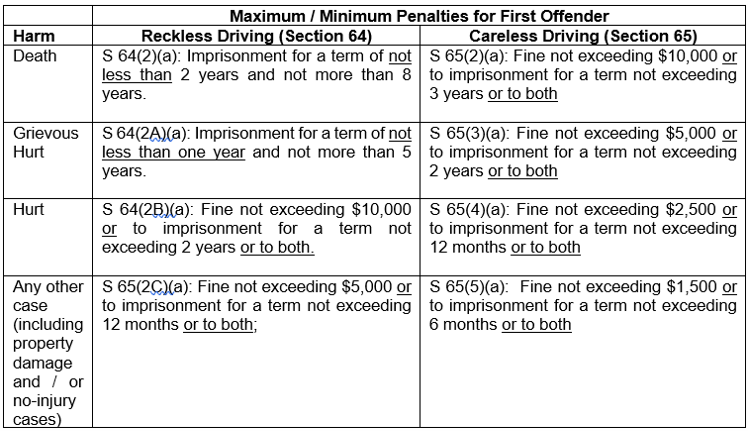

The table below lays out the minimum / maximum fines / terms of imprisonment for the offences of Reckless and Careless driving (not including any period of disqualification from driving which may be imposed). It may be observed that for certain levels of harm, the offence of Reckless Driving can carry mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment.

The Courts’ Approach to Sentencing

It is not possible here to lay out all of the possible considerations a sentencing Court may take into account. At this time of writing, the judicial approach to sentencing for Careless and Reckless driving appears to still be undergoing development.

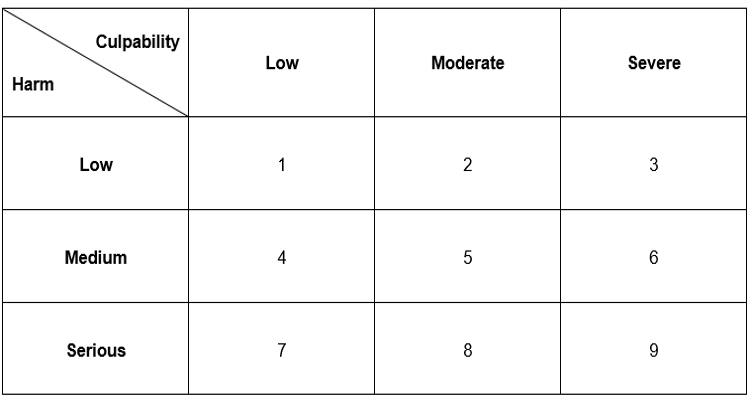

Generally, the Courts tend to begin by considering the level of Harm caused, and the Culpability of the Offender to determine the starting sentence. A crucial consideration is whether the case warrants a jail term or whether a fine is sufficient where there is no mandatory imprisonment. This is called the “custodial threshold” which is often a foremost consideration to potential offenders.

There is case law to suggest that at least for the offence of Reckless Driving, the custodial threshold is not usually reached in cases where the level of Culpability lies between low to moderate and the degree of Harm is between low to medium (i.e. boxes 1, 2, and 4 but not 5 in the table below), if there are no aggravating factors. However, each case will be determined on their own facts.

The level of Harm and Culpability are assessed on a case-by-case basis. For Culpability, conduct which tends to fall within the low to moderate range includes behaviour such as beating a red light. If there are multiple breaches of safe driving practices, it may be expected that Culpability will be higher, and where very dangerous conduct such as driving under the influence or road racing is concerned, these factors may push Culpability into the severe range.

For Harm, naturally if death is caused, it will fall within the serious range. Where victims have suffered multiple fractures or a degree of severe permanent injury, Courts have also tended to assess Harm at between the moderate to serious ranges. On the other hand, where there are no fractures or severe injuries, Harm tends to fall at the low end. It should be noted that potential harm to other road users is also accounted for in this analysis.

After the Court has decided its starting sentence, including whether or not a sentence of imprisonment is warranted, then the Court will adjust the sentence based on other relevant aggravating and mitigating factors. Some examples of other aggravating factors include whether the offender has a record of past driving offences.

In conclusion, understanding the law behind the offences of Reckless and Careless Driving can be a complicated and stressful procedure. The law is also continually developing in this regard, and the best advice one should walk away with is to drive safely and with proper consideration for the rules and for other road users.

In the July 2022 Singapore High Court (“SGHC”) decision in Public Prosecutor v Manta Equipment (S) Pte Ltd [2022] SGHC 157 (“Manta”), the SGHC reviewed the existing legal position on sentencing for offences committed under Section 12(1) of the Workplace Safety and Health Act 2006 (the “Act”). In so doing, the SGHC harmonised the divergent sentencing approaches in existing case law, and developed a new sentencing framework to be applied in cases where a body corporate is charged with offences under Section 12(1) of the Act.

To elaborate, Section 12(1) of the Act imposes a duty on every employer to “take, so far as is reasonably practicable, such measures as are necessary to ensure the safety and health of the employer’s employees at work.” A contravention of Section 12(1) is an offence, pursuant to Section 20 of the same Act.

Notably, the structure of the Act makes it possible for an officer of a body corporate to be charged and found guilty of an offence under Section 12(1), pursuant to Section 48(1) of the Act. Furthermore, while a body corporate may be liable to a fine not exceeding $500,000.00, an officer may be liable to a fine not exceeding $200,000.00, or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 2 years, or to both.

Given the recently reported rise in offences under the Act in Singapore, officers of bodies corporate (such as directors or company secretaries) which find themselves at risk contravening Section 12(1) of the Act may wish to pay close attention to legal developments which flow from Manta. This is because, at the time of writing, there have been no reported decisions where the Manta sentencing framework has been modified to apply to a human officer for an offence under Section 12(1) of the Act.

Characterist LLC has recently had the opportunity to render our services to a client, who is a director of a construction company who had pleaded guilty to offences under Section 12(1) of the Act. In making our legal submissions on sentencing, we broached new grounds in being one of the first law firms to apply the Manta sentencing framework in a modified form to an accused person who was a human officer of a body corporate.

At the conclusion of our submissions, the Honourable Court ultimately adopted a proportional approach to sentencing, wherein the starting point was that the fine imposed on a human officer would lie at around 40% of that which would be imposed on a body corporate under the Manta sentencing framework. The basis of this position was that the maximum fine a company could face is $500,000.00 under the Act whereas a human officer would face a maximum fine of $200,000.00.

Although our work covered new and barely explored legal territory, the full impact of the Manta decision remains to be seen. Some open questions that remain include, for officers of bodies corporate, when it would be appropriate to impose a term of imprisonment for an offence under Section 12(1) of the Act, and whether the imposition of imprisonment should have any bearing on the fine (if any) that might be simultaneously imposed. These questions will have to be answered over the course of the incremental development of case law in time to come.

CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGE AGAINST VDS AND WVM (HC/OS 156/2022) – LOCUS STANDI, REAL CONTROVERSY AND PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE WHEN MEASURES ARE PARTIALLY DROPPED

INTRODUCTION

This update provides a commentary on the Singapore High Court’s recent decision (made in respect of two interlocutory applications filed in HC/OS 156/2022 (“OS 156”)) on the standing / “real controversy” requirement in the context of constitutional challenges against vaccine-differentiated safe management measures (“VDS”) and Workforce Vaccination Measures (“WVM”), where the law, policies, regulations, statistics and science are constantly evolving.

In particular, where an applicant has standing at the time of filing a constitutional challenge, does the applicant lose that standing with respect to the VDS / WVM which are dropped prior to the Court hearing? If so, what are the practical implications arising from this?

Characterist LLC’s Dominic Chan, Daniel Ng and Daniel Goh acted for the five Applicants in OS 156.

OS 156 – CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND JUDICIAL REVIEW CHALLENGE AGAINST VDS AND WVM

On 18 February 2022, five Applicants filed a constitutional law and judicial review challenge (i.e. OS 156) against VDS (in relation to unvaccinated1 citizens) and WVM (in relation to unvaccinated workers).2

The challenge was based on the Applicants’ constitutional rights of freedom of movement, right to life or livelihood, freedom of assembly, equal protection and freedom of religion (see Annex A of the downloadable PDF for a summary of the arguments set out in the Statement in support of OS 156). The affidavits of the Applicants, followed subsequently by the expert affidavits of Dr. Harvey Risch and Dr. Peter McCullough (opining on inter alia the efficacy and safety profile of the Covid-19 mRNA vaccines), were filed in support of OS 156.

26 APRIL 2022 STOOD DOWN MEASURES, AMENDMENT AND STRIKING OUT APPLICATIONS

Before OS 156 was heard, on 22 April 2022, the MTF announced that it would be easing VDS measures from 26 April 2022, by lifting WVM and removing VDS from all settings save for 4 settings (“Stood Down Measures”)3. In the light of this development, the Applicants filed an amendment application (HC/SUM 2073/2022)4, while the Attorney-General (the “Respondent”) filed a striking out application (HC/SUM 2295/2022).

HEARING BEFORE THE AR, CENTRAL ISSUE, AND THE PARTIES’ KEY ARGUMENTS

Both applications were heard before an Assistant Registrar (the “AR”) on 12 August 2022. The central issue was whether the Applicants, who had standing when they filed the OS, continued to have standing (in latin, “locus standi”) to challenge the Stood Down Measures. One critical element of locus standi, is that there must be a “real controversy” between the parties. This element goes to the Court’s discretion, and not jurisdiction.5 “Where the circumstances of a case are such that a declaration will be of value to the parties or to the public, the court may proceed to hear the case and grant declaratory relief even though the facts on which the action is based are theoretical.”6

Respondent’s Arguments: The Respondent’s central argument (amongst other arguments) is that in the light of the Stood Down Measures, OS 156 had become hypothetical, academic or moot with respect to the Stood Down Measures, that there was no “real controversy” remaining between the parties and the Applicants no longer have standing in this regard, and therefore, the striking out application should be allowed. The Respondent made no submissions on: (1) the constitutionality of VDS / WVM; (2) the reasonableness or rationality of VDS / WVM (from an administrative law standpoint); or (3) the efficacy or safety profile of the Covid-19 vaccines.

Applicants’ Arguments: The Applicants argued (amongst other arguments) that the primary relief sought under the proposed amended OS, namely, a vindication of the Applicants’ constitutional rights, have substantial, personal and/or practical significance to the Applicants. In particular, the declaratory relief sought will be of great importance to the Applicants for the purposes of reversing or removing the stigma and ostracization (which the Applicants face)7, as well as various harms,8 which was set in motion, caused or contributed to by VDS / WVM, and which continue to remain notwithstanding the Stood Down Measures. In this regard, the Applicants pointed out to inter alia the following:

(1) Stronger Stance: The Ministry of Health’s press release “Calibrated Adjustments in Stabilisation Phase” (8 November 2021) where they stated:

“We are taking a stronger stance against those who choose not to be vaccinated, be it through the VDS, or by requiring them to pay for their medical bills.”9

(2) Step Down but Not Dismantle: The MTF had expressly reserved the right to implement and/or step up VDS or WVM again depending on the situation. In summary, the MTF had taken a “step down but not dismantle” posture (see e.g. the MTF’s 22 April announcement, and the Minister of Health’s statement made in Parliament on 9 May 2022). These statements confirm that VDS and/or WVM may come back, either in full force or in part.

(3) VDS which Remained in Force: The 4 Remaining VDS continued to remain in force.

(4) Empower, Embolden, Encourage: The Ministry of Manpower (“MOM”)10 had stated on 25 April 2022 (see the “Updated Advisory on COVID-19 Vaccination at the Workplace” dated 25 April 2022 (“25 April 2022 Workplace Advisory”)) that employers may continue to implement VDS and/or WVM on their own accord,11 thereby effectively making vaccination status an acceptable or permitted ground of discrimination for hiring. The Applicants submitted that this has or will effectively empower, embolden and/or encourage employers to continue the imposition of VDS and/or WVM against unvaccinated workers (including some of the Applicants) in various circumstances in terms of current and/or future employment.

(5) Cloud of Fear and Uncertainty: In addition, in the light of the above, the Applicants continued to live under a cloud of fear and uncertainty that VDS / WVM may come back anytime to severely and suddenly upend their lives (and their families’ lives) again

THE AR’S DECISION, THE APPEALS AND SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS

At the hearing of the applications on 2 September 2022, the AR preferred the Respondent’s arguments over the Applicant’s arguments, and followed various recent UK and Canadian court decisions cited by the Respondent12 over various Malaysian and US cases cited by the Applicants.13 Accordingly, the AR disallowed the Applicants’ amendment application, and struck out OS 156, save for the dining VDS under OS 156 (in respect of which the Respondent did not challenge the Applicants’ standing).

The Applicants appealed to a High Court Judge in chambers, and the appeals were fixed for hearing on 18 October 2022.

On 7 October 2022, the MTF announced that they “will lift VDS fully” from 10 October 2022.14 On 7 October 2022, the MOM15 also updated its advisory on Covid-19 vaccination at the workplace (“7 October 2022 Workplace Advisory”).16 In the light of these latest developments, the Applicants withdrew the appeals and OS 156.

COMMENTARY

First, it is important to note that the various announcements of the MTF and related ministries, including the ones which communicate clear decisions implementing VDS / WVM, are not susceptible to judicial review or constitutional challenge until and unless they are enshrined in subsidiary legislation or regulations.17 This is because until such time, they do not have legal effect. This legal position is different from how the average layperson would likely perceive the way Covid-19 measures have been implemented. Even though the enshrining of VDS / WVM in the various regulations typically takes place a few days after each announcement of the MTF, and appear to be mere formalities flowing from clear executive decisions, the legal position established by the Singapore courts is that only the legislation or regulations are susceptible to judicial review.

Second, and flowing from the first point above, it is dissatisfactory that weighty advisories (made by the MOM amongst others) such as the 25 April 2022 Workplace Advisory are not susceptible to court challenge,18 especially insofar as it had or would have had an impact on how employers behaved vis-à-vis their unvaccinated employees and thus affecting actual legal rights, albeit indirectly. Importantly, insofar as such an advisory has had the effect of perpetuating the stigma and ostracization which unvaccinated workers faced in terms of current and/or future employment, Singapore’s narrow approach to the “real controversy” issue, whereby locus standi to challenge the constitutionality of WVM was lost due to the revocation of the regulations embodying WVM, would make it exceedingly difficult for such workers to seek redress from the Court.

Third, given that standing may be lost once the regulations (embodying the VDS and/or WVM) being challenged are revoked, insofar as VDS and/or WVM are reimplemented (whether in a similar or different form), it is imperative for any future constitutional challenge and/or judicial review application to be filed, and heard and determined on an urgent and expedited basis.19 This would mean that interested applicants would have to marshal substantial resources very quickly, to prepare their case based on the latest laws, policies, facts, statistics and/or expert scientific evidence.

The Health Minister Mr. Ong Ye Kung has said that “when the situation requires, we may have to step up VDS to an appropriate level, in order to protect those who are not up to date with their vaccination.”20 There is a real likelihood that VDS and/or WVM, in various permutations or forms, may continue being reimplemented in the future. They may also be revoked at short notice, thereby making any substantial constitutional and/or judicial review by the Court highly elusive. To ensure that the Court is able to engage in any substantive constitutional and/or judicial review of VDS and/or WVM, the law effectively requires any applicants to proceed on an expedited basis, and to seek urgent hearing dates as far as possible.

Footnotes

1 By virtue of the Government’s definition of being fully vaccinated, VDS and WVM had applied not only to unvaccinated persons, but also to partially vaccinated persons, those who did not qualify for medical exemptions, as well as vaccinated persons who did not receive their necessary booster to maintain their vaccination status.

2 VDS and WVM as announced by the Multi-Ministry Taskforce (“MTF”) and related ministries on 6 August 2021, 9 October 2021, 23 October 2021, 20 November 2021, 14 December 2021, and 26 and 27 December 2021 (collectively, the “Decisions”), and embodied in inter alia the following regulations: (1) Workplace Safety and Health (COVID-19 Safe Workplace) Regulations 2021, Regulations 9 to 13, and 30; (2) Infectious Diseases (COVID-19 Access Restrictions and Clearance) Regulations 2021, Regulations 6, 7A, and 9, and the Second Schedule; (3) COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations 2020, Regulations 6 and 8, and the First Schedule and Third Schedule; (4) COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Sporting Events and Activities – Control Order) Regulations 2021, Regulations 5, 7, and 14; (5) COVID‑19 (Temporary Measures) (Business Events — Control Order) Regulations 2021, Regulations 4 and 8; (6) COVID‑19 (Temporary Measures) (Performances and Other Activities — Control Order) Regulations 2020, Regulations 7A, 12A, 14, and 21A; (7) COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Religious Gatherings — Control Order) Regulations 2021, Regulations 8, 15, and 28A (collectively, the “Statutes / Regulations Embodying the Decisions”).

3 Namely, (1) Events with more than 500 participants at any one time; (2) Nightlife establishments where dancing among patrons is one of the intended activities; (3) F&B establishments, including restaurants, coffeeshops and hawker centres; and (4) Casinos (collectively, the “4 Remaining VDS”).

4 To pivot the main relief sought, from a quashing order (a remedy under judicial review) to freestanding declaratory relief (under O.15, r.16 of the Rules of Court, 2014) on the constitutionality of VDS / WVM (with respect to the Stood Down Measures, as well as the 4 Remaining VDS) as the main relief (in the original OS 156, this was a further relief sought under the facilitative provision under Order 53 of the Rules of Court, 2014), while maintaining the prayer for a quashing order with respect to the 4 Remaining VDS.

5 Tan Eng Hong v Attorney-General [2012] 4 SLR 476 (“Tan Eng Hong”) at [115] and [137].

6 Tan Eng Hong at [143].

7 Namely, that VDS and/or WVM exposed the Applicants to alienation, segregation, marginalization, ridicule, contempt and/or avoidance by or from the rest of society, effectively making them into 2nd class citizens and/or a new substratum of society.

8 See [6] of Annex A of the downloadable PDF for an elaboration of such harms.

9 Emphasis in bold added.

10 Together with the National Trades Union Congress (“NTUC”) and the Singapore National Employers Federation (“SNEF”), etc.

11 The material portions of the 25 April 2022 Workplace Advisory (at [6]) include: “Taking into consideration the workplace health and safety and operational needs of their respective companies or sectors, employers may implement vaccination-differentiated requirements for their employees (such as disallowing unvaccinated employees from entering the workplace), as a matter of company policy and in accordance with employment law. For unvaccinated employees whose jobs require working on-site as determined by the employers under such a company policy, employers may … [redeploy them or place them on no-pay leave based on mutually agreeable terms, or]… As a last resort after exploring options above, terminate their employment (with notice) in accordance with the employment contract. If the termination of employment is due to employees’ inability to be at the workplace to perform their contracted work, such termination of employment would not be considered as wrongful dismissal.” [Emphasis in bold added].

12 The applicants in the UK and Canadian cases were held to have lost their standing to challenge the COVID-19 regulations once they had been removed from the statute books.

13 In the Malaysian case, the Court held that a person had standing to challenge a revoked criminal law even after it had been repealed, while in the US case, the Court held that the applicant had standing to challenge the revoked COVID-19 visitor policy (barring Catholic clergy from ministering in-person to the spiritual needs of inmates) even after it had been removed (the AR held that this case was of limited relevance to the present matter, as, amongst other things, the standard for finding that a case is justiciable under US law appears to be different from Singapore law).

14 The MTF elaborated that this “means that VDS will no longer be required for (i) events with more than 500 participants at any one time, (ii) nightlife establishments where dancing among patrons is one of the intended activities, and (iii) dining in at F&B establishments, including hawker centres.”

15 Together with the NTUC and the SNEF, etc.

16 Amongst other things, the 7 October 2022 Workplace Advisory provides (at [4]-[5]) that:

“4. With the lifting of VDS, the tripartite partners are of the view that employers should take the decision to remove vaccination-differentiated requirements for access to the workplace. However, employers may consider whether the situations in para 5 below are applicable.

Vaccination-differentiated requirements for specific occupations

5. If there are genuine occupational requirements, employers, taking into consideration the workplace health and safety and operational needs of their business, may continue implementing vaccination-differentiated requirements for their employees to access the workplace (such as deploying only vaccinated individuals), as a matter of company policy and in accordance with employment law. For example, employers may require their employees to be fully vaccinated before entering the workplace because their employees have to work closely with vulnerable individuals (which may be the case for allied healthcare professionals, nurses and doctors in hospitals and clinics); or the employees’ job scope involves travelling to countries with vaccination-differentiated entry requirements.”

[Emphasis in bold original].

17 The AR applied Han Hui Hui and ors v Attorney-General [2022] SGHC 141 (“Han Hui Hui”) at [58]-[59] (see footnote 18 below for an elaboration), and held that the prayers to challenge inter alia the Decisions of the MTF do not disclose any reasonable cause of action and should be struck out.

18 In this regard, see Han Hui Hui at [58]-[59], where the High Court held that the “Updated Advisory on COVID-19 Vaccination at the Workplace” dated 23 October 2021 (the “October Advisory”) does not amount to a policy directive, nor does it carry legal effect. It is also not the source of any legal obligations to comply with the WVMs as it merely reiterated the Government’s announcement of the WVMs. The WVMs were instead implemented by subsidiary legislation and derive their legal force from them. For the lack of legal effect, the October Advisory cannot be subject to a quashing order. Applying Han Hui Hui, as well as the AR’s decision (applying Han Hui Hui at [58]-[59]) that even the MTF’s Decisions do not have legal effect and cannot be subject to a quashing order (see footnote 17 above), the 25 April 2022 Workplace Advisory would likewise lack legal effect, and cannot be subject to a quashing order.

19 In this regard, see [31]-[32] of R (on the application of Hussain) v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care [2022] EWHC 82:

“31. … Whether expedition and an urgent rolled up hearing would be appropriate in the context of any future PCW [i.e. prohibition on collective worship, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic in UK, in conjunction with the “lockdown”] and any future prompt challenge to its legality invoking Article 9, is an open question. But if those steps are appropriate in those future circumstances, in the judgment of the Court dealing with that situation, then they will be granted.If they are not granted, it is because they are not appropriate. That is as it should be. There is nothing here approaching any deficit in the Court’s ability to provide an appropriate response which would justify, in the public interest, allowing the present claim to proceed by means of an “historic” analysis of the justification for the PCW in the circumstances as they were in and after March 2020 or May 2020. The correct position in principle is – and has to be – that the Courts have, and will always seek to discharge, the responsibility of delivering practical and effective justice, consistently with the overriding objective…

32. A claim challenging a future PCW – if the Claimant considers a challenge to be justified and if he seeks his ‘day in court’ – could be pursued with conspicuous and demonstrable promptness, pointing to all these considerations. Instead of pressing for interim relief, the Claimant could be asking for the Court’s resources to be channelled into an expedited ‘rolled-up’ hearing. There would need to be a reworked JRG [i.e. judicial review grounds]. But that is as it should be, to ensure a disciplined focus and to engage judicial review remedies designed to be practical and effective. The Court will respond in the way that it judges promotes the interests of justice and the public interest. That is a good and sufficient answer … This is an important recognition. If there were to be a future PCW, and if the Claimant sought promptly to challenge its Article 9 compatibility, the Defendant would need to think carefully about what position it takes in the proceedings – given the duty of (candour and) cooperation – so far as concerns the facilitation of prompt resolution of the substantive legal merits.”[Emphasis in bold added]

20 See [19] of the Minister’s Opening Remarks at the MOH Press Conference to Update on the Covid-19 Situation on 15 October 2022.

Injured workers who suffer an accident while arising out of and in the course of their employment have the option of bringing a claim under:-

- The Work Injury Compensation regime, codified through the Work Injury Compensation Act (“WICA”); or

- Common Law by commencing a claim in the Singapore Courts.

This does not only refer to an industrial or workplace accident, but (depending on the transport arrangement between the employee and his employers) may also include a road traffic accident that occurs while an employee is travelling to or from his place of work. A claimant ultimately has to decide whether to resolve / settle a claim under WICA or Common Law – he cannot obtain both.

In this article, we aim to highlight and discuss several pertinent pros and cons that a typical claimant may experience if he were to choose to pursue a claim using either WICA rules or Common Law, using the lenses of liability, quantum and procedural duration. However, as the ultimate inquiry is often highly factually specific, we would refrain from expressing any general preference or broad view on what may be more advantageous to a potential claimant. This article also does not address issues of insurance coverage or the enforceability of any award / judgment obtained.

WICA claims

(i) Liability under WICA

The High Court has previously described the WICA as “social legislation” that should be “interpreted purposively in favour of employees who have suffered injury during their employment” (see Pang Chew Kim v Wartsila Singapore Pte Ltd, [2011] SGHC 94; [2012] 1 SLR 15 at [27]). In effect, this often means that once a claimant can show that he comes under the WICA ‘umbrella’, there is no need to show negligence or any other legal fault on the part of the employers. This also means that a claimant under WICA is not penalized for contributory negligence on his own part leading towards the accident. All things being equal, a claim may be easier to establish / sustain under WICA than under Common Law.

(ii) Quantum under WICA

Apart from medical expenses and loss of wages while on medical leave, the quantum of compensation in a WICA claim is usually determined based on the tables set out in the Third Schedule of the WICA. 3 main factors are relied on to determine the compensation amount:-

- The claimant’s age on the next birthday;

- The claimant’s average monthly salary; and

- The percentage of permanent total incapacity (or death) resulting from the claimant’s injuries, as assessed by a medical professional.

The assessment of compensation under WICA is subject to statutory minimum and maximum limits that are reviewed from time to time.

(iii) Procedural duration

In ordinary WICA proceedings, an injured employee should notify the employers of the accident as soon as practicable, and a formal claim should be initiated within 1 year of the accident causing the injury (or, in the case of death, 1 year the date of death).

When the relevant income documents have been submitted and medical assessment has been prepared, the Ministry of Manpower can conduct a computation of the compensation amount due to the claimant. If either party objects to the computation, an inquiry process is initiated culminating in a formal hearing to determine the claim. All things being equal, a WICA claim usually concludes faster than a contested Common Law claim.

Common Law claims

(i) Liability at Common Law

Claims for personal injury under Common Law are usually founded upon the tort of negligence. In order to succeed, a claimant has to show that on a balance of probabilities, the Defendant(s) owed him a duty of care, had breached or failed to meet the reasonable standard of care expected of them and that this breach has caused damage (or injury) to him. As alluded to above, if the claimant is found to be partially at fault for causing the accident, a measure of contributory negligence may be attributed to him. If for example the Court finds that a claimant should bear 20% contributory negligence, then he will only be able to obtain 80% of the damages that are eventually assessed.

(ii) Quantum under Common Law

A claim under Common Law is usually assessed for general damages and special damages. Common heads of general damages include pain and suffering for injuries sustained, loss of earning capacity and/or loss of future earnings and future medical expenses. Common heads of special damages include incurred medical and transport expenses, as well as pre-trial loss of earnings or any other directly quantifiable losses that can be proved with supporting documents. All things being equal, the quantum of a Common Law claim may be higher than a WICA claim (subject to any percentage of contributory negligence that a claimant has to bear).

(iii) Procedural duration

For Common Law claims under the tort of negligence involving personal injury, a claimant has 3 years from the date of the accident to initiate a claim. The duration of a Common Law claim can vary greatly, depending on factors such as the complexity of the legal issues that need to be covered, the parties involved or the availability of documents etc. Most cases in Singapore are resolved at a pre-trial stage whether through parties’ negotiations or with the assistance of the Court-led mediation process. Where claims cannot be settled through through mediation or other negotiations, the Court will arrange for a trial where witnesses will attend to give their evidence. On average, a contested Common Law claim may take at least 12 to 15 months before liability and quantum are decided.

Conclusion

Both the WICA regime and Common Law claims offer potential claimants a viable route to obtain compensation for injuries suffered further to a work-related accident. If a potential claimant is faced with a choice between the 2, the pros and cons to be weighed often depend heavily on the factual circumstances at hand as these would affect the potential outcomes on liability and quantum. It would be best for a potential claimant to obtain legal advice on his intended course of action, so that an informed decision can be made taking into account the relevant facts, individual preferences and the various nuances that may be encountered.

Landlord-tenant disputes are surprisingly common. Most of the time, the dispute begins with a tenant who defaults on rent, and the landlord is then put in a position of deciding whether to take formal steps to recover the rent, or perhaps even to terminate the lease.

In this article we will set out various types of solutions available to landlords, and the circumstances in which each one is most suitable.

Solution 1: Writ of Possession

As its name suggests, a Writ of Possession allows a landlord to recover vacant possession of the rental premises. A Court-appointed bailiff will attend at the premises and require the tenants to leave the premises.

This solution is most suitable for a landlord who has already decided to terminate the lease, and wishes to cut its losses by having the tenant vacate the premises as soon as possible. While changing the locks seems like an easier and cheaper solution, this is not advisable if the tenant is still occupying the premises, or if the tenant’s belongings are still in the premises. Doing so can expose the landlord to civil liability for false imprisonment or for damage to the tenant’s items.

Where a tenant refuses to vacate the premises, or where the landlord is unsure if the tenant has abandoned the premises, the Writ of Possession is most effective in enabling the landlord to regain access to the premises via legal means.

If a landlord only wishes to recover unpaid rent, but is willing to let the tenancy continue, a Writ of Possession will not be applicable. This brings us to the next solution.

Solution 2: Writ of Seizure and Sale

A Writ of Seizure and Sale is useful where a landlord wishes to recover unpaid rent.

In this instance, a Court-appointed bailiff will attend at the premises, seize items of value, and sell these items at an auction. The auction proceeds can then be used to repay the landlord. Depending on the value of the items and the amount of rent outstanding, the landlord may or may not recover a substantial amount of unpaid rent.

Often, a Writ of Possession is applied for together with a Writ of Seizure and Sale in order to allow a landlord to recover vacant possession of the premises as well as to recover unpaid rent.

If a landlord is willing to let the lease continue, and simply wishes to recover unpaid rent, the landlord can apply for a Writ of Seizure and Sale alone. Alternatively, the landlord can consider the next solution below.

Solution 3: Writ of Distress

Like a Writ of Seizure and Sale, a Writ of Distress allows a Court-appointed bailiff to attend at the premises and seize items of value. If the tenant does not pay the outstanding rent and all other fees associated with the Writ of Distress within 5 days, the bailiff will sell the items at an auction. The auction proceeds can then be used to repay the landlord.

This option is only applicable to a landlord who does not intend to terminate the lease, but wants to recover unpaid rent.

Pre-solution Steps

Before taking any of the steps above, a landlord should obtain a Court judgment stating what reliefs the landlord is entitled to. These reliefs include payment of the unpaid rent, or recovery of vacant possession of the premises.

Depending on which steps the landlord chooses to take, the landlord may also need to seek leave from the Court before applying for any or the above Writs.

As the application for the various Writs can be rather technical, we suggest that a landlord seek legal advice in order to ensure that all procedural requirements are met and that recovery can take place smoothly.

Other Considerations

In asking the question of which solution to employ, one of the landlord’s considerations would be the remaining duration of the lease.

If a tenant defaults on his rent early in the lease, a landlord may wish to take steps to recover unpaid rent early, but may be willing to let the tenancy continue. In this instance, a Writ of Distress may be most appropriate.

If the landlord wants to cut its losses and avoid future problems by terminating the tenancy, a Writ of Possession is often most helpful, especially when coupled with a Writ of Seizure and Sale.

If only a few months are left of the tenancy, a landlord who prefers not to incur costs on legal proceedings may wish to wait it out rather than applying for a Writ of Possession, in the hope that the tenant will automatically leave the premises at the end of the tenancy. However, if the amount of unpaid rent is significant and exceeds the security deposit sum, the landlord may want to apply for a Writ of Distress to recover the unpaid rent in the meantime.

Where a Tenant Pays

At times, when faced with formal Court proceedings and the prospect of eviction, a tenant may decide to make payment of all unpaid rent and other costs incurred by the landlord, in order to avoid further proceedings. This can happen as late as after the landlord obtains a judgment stating that the landlord is entitled to vacant possession and repayment of rental arrears, or just before eviction.

The law provides that when a tenant makes payment of all such sums within certain stipulated periods of time, the landlord cannot continue taking steps to evict the tenant. For instance, the Writ of Possession provides for a 4-week period to allow the tenant to pay all outstanding sums and avoid eviction.

Conclusion

In the face of a defaulting tenant, a landlord will ultimately have to take into account various considerations in deciding what steps would be most suitable. This includes timing and the lease duration, how much the landlord is willing to incur in costs, whether the landlord is keen to take out formal proceedings, and whether there is a possibility that litigation can be avoided.

If you have any uncertainties as to the options available to you, and which would be most ideal in your situation, do seek advice from a lawyer.

Introduction

In this article, I wish to share some insights about what to look for when you ask someone to hold shares in a company for you. Such an arrangement is often called a nominee shareholder arrangement.

Reason for such arrangements

The person who is named as the owner is the nominee while the person who actually paid for the shares is the beneficiary. The beneficiary often feels that there is a need to be not named on the register of members as a shareholder and hence enters into such an arrangement.

Uses

The main use is that the actual beneficial owner of the shares will not be seen to be on the public records as a shareholder of the relevant company. This can give a measure of privacy and confidentiality. There are other methods such as setting up intermediary companies though these methods might cost more to implement than a nominee shareholder arrangement.

Pitfalls

Most of the pitfalls in such an arrangement arise from the fact that the nominee is put in a position of control of the rights that attach to the relevant shares; in addition, the company is not required by law to recognise any trustee or nominee shareholding arrangement.

Some of the common pitfalls that I have seen in my several years of practice are as follows:

- The legal owner or nominee refuses to return the shares to the beneficiary.

- The legal owner exercises the rights or enjoys the rights attached to the shares without the consent or knowledge of the beneficial owner. In particular, he uses the shares as security or sells them.

- The legal owner passes away or is deregistered and the beneficial owner is unable to get the shares transferred to himself.

Some Solutions

The solutions that I have recommended and implemented in the past aim at eliminating the possibility of the nominee exercising rights over the shares that he is not entitled to exercise and at the very least ensure that the arrangement is in written form and can be produced as evidence.

Firstly, it is essential that a nominee shareholder agreement with clear and adequate provisions for the beneficiary be prepared and stamped with the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore or relevant tax office of the country where the shares are located. Stamping is essential in Singapore so that the nominee shareholder agreement can be produced in the Singapore courts as evidence.

However, based on experience and consideration of the risks concerned, a signed and stamped nominee shareholder agreement alone is not sufficient, even if it contains undertakings by the nominee to not exercise rights attached to the shares. As many unfortunate beneficiaries in such arrangements can attest, the nominee may choose to breach the agreement.

There are other documents and practical steps that can be prepared and taken and we have advised on and implemented such steps for beneficiaries before. Some of these involve amending the company’s constitution and taking necessary actions with the share certificates.

Conclusion

Although the nominee shareholder arrangement is straightforward conceptually, it actually involves risks for the beneficiary which should be dealt with strongly failing which the beneficiary may find himself having to commence proceedings to assert his rights and ownership.

The arrangement can be likened to a situation where someone passes physical possession of a valuable to another person. The beneficial owner must ensure that the person who has possession does not seek to enjoy rights that he is not entitled to enjoy, and that he can get the property back easily when he wants to.

Ever since the Additional Buyers’ Stamp Duty (“ABSD”) rates increased substantially on 6th #425563;”> July 2018, the demand for decoupling, property purchases under trust and consultations for advance planning of intended property purchases has steadily increased.

A Singaporean buying a subsequent residential property is now levied ABSD of 12% for the second property and 15% for the third and subsequent property. A Permanent Resident pays ABSD at 5% for the first residential property and 15% for the second and subsequent property. ABSD rates have increased three times since 2011. It is not surprising that many property buyers are keen to find ways to reduce ABSD.

There are generally 3 ways to avoid or reduce the amount of ABSD payable on subsequent residential property purchases.

- Decoupling

These are some potential costs to be taken into consideration in decoupling:-

- the Transferor may be subject to Seller’s Stamp Duty on the share transferred if the Transferor purchased the property less than 3 years ago;

- ABSD is payable on the value of the share transferred if the Transferee has more than one property;

- if the decoupling transaction is done within the lock-in period for the bank loan, then the bank may charge a penalty;

- if the Transferor had initially used CPF funds in purchasing the property, the CPF funds and accrued interest have to be refunded into his CPF account. Usually, the Transferee would obtain a fresh loan to pay for the purchase of the share transferred in his favour. From the proceeds of the sale, the Transferor would refund his CPF monies, pay for his share of the outstanding bank loan and retain the balance. The fresh loan obtained by the Transferee should be in a quantum that is also sufficient to refinance the Transferee’s own share of outstanding bank loan; and

- the total legal costs will be about $5000 to $6000.

For example, Mr. Tan and Mrs. Tan (both Singapore Citizens) had 3 residential properties in their joint names. They wished to upgrade one of the properties to a bigger property. This was their course of action:-

- Sell Property A. Hence, they were left with 2 properties in their joint names;

- Decouple Property B. Mrs. Tan bought Mr. Tan’s share.

- Decouple Property C. Mrs. Tan bought Mr. Tan ‘s share.

- Mr Tan bought Property D as his 1st property.

Sale of Property A

Mr and Mrs Tan sold Property A. After their buyer exercised the option to purchase, Mr and Mrs Tan’s property counts reduced from 3 to 2.

Decoupling Property B

Mr. Tan sold his half share to Mrs. Tan. The property was valued at $1.5million. Hence, the sale price was $750,000.00. The property was bought more than 3 years ago and the bank loan was not subject to any lock in period.

Seller’s Stamp Duty NA Bank Loan Penalty NA *BSD based on the price $750,000.00 $17,100.00 ABSD $90,000.00 Legal cost $5,500.00 Total decoupling cost $112,600.00 *BSD is the standard stamp duty payable on every purchase. BSD Rates are based on the purchase price or the market value of the property, whichever is the higher. BSD Rates for residential property is calculated at 1% for the first $180,000, 2% for the next $180,000, 3% for the next $640,000 and 4% for the remaining amount.

Decoupling Property C

Mr. Tan sold his half share to Mrs. Tan. The property was valued at $2million. Hence, the sale price was $1million. The property was bought more than 3 years ago and the loan was not subject to any lock in period.

Seller’s Stamp Duty NA Bank Loan Penalty NA *BSD based on the price $1,000,000.00 $24,600.00 ABSD $120,000.00 Legal cost $5,500.00 Total decoupling cost $150,100.00 Purchase Property D

After the decoupling of Property B and Property C, Mr. Tan ‘s property count reduced from two to zero. Hence, his purchase of Property D for $5.5million was considered his first property and did not attract any ABSD. By arranging for decoupling, he enjoyed substantial savings of $562,300.00.

ABSD saved (15% of purchase price) $825,000.00 Less decoupling cost of Property B $112,600.00 Less decoupling cost of Property C $150,100.00 Total savings $562,300.00 If Mr. Tan had done decoupling for only Property B, then his purchase of Property D would be considered a second property and attract ABSD at 12%. He would still enjoy savings, although much less substantial.

3% of ABSD saved (he pays 12% instead of 15%) $165,000.00 Less decoupling cost of Property B $112,600.00 Total savings $52,400.00 When decoupling is not a suitable solution

Generally, decoupling does not make sense if the next property to be purchased is lower in value than the value of the share transferred in decoupling since there are no savings.

Since April 2016, HDB flat owners are not allowed to transfer their ownership to a family member except on grounds of divorce, marriage, death of an owner, financial hardship, citizenship renunciation and medical reasons. As such, decoupling would usually not work for HDB flats.

- Purchase under trust

Another way of reducing ABSD is to purchase the next property on trust for a beneficiary with zero property count. If the beneficiary has zero property count, no ABSD is payable. There has been an increase in clients purchasing properties on trust for their children. These clients would appoint themselves as trustees who have legal ownership and control of the property. As trustees, they have fiduciary duties to manage and administer the property for the benefits of the beneficiary.

There are benefits to this arrangement.

- The property held on trust is shielded from division upon the divorce of the trustor. i.e. the person who establishes the trust. This means the property set aside in the trust for the child will never be subject to division on the trustor’s divorce. This protection cannot be secured by a will, which can be revoked any time.

- It is also shielded from division upon the divorce of the beneficiary. This is useful for those who wish to give their assets to a child with assurance that the gift will not be distributed to unintended third parties if the child eventually marries and divorces.

- The beneficiary may be a minor i.e. below 21 years of age. There is no restriction on the minimum age of the beneficiary.

- The trust need not to be registered and hence confidentiality may be maintained.

- This arrangement is inexpensive. Legal costs is about $2,500 onwards depending on the terms of the trust.

At present, in Singapore, banks do not grant loans for properties bought on trust. It is therefore not uncommon to see a trustor mortgaging his existing property to raise funds for buying a property on trust.

- Plan ahead, buy in the right name and shareholding

Whenever it is financially viable, properties may be bought in sole names.

If this is not possible (for example, the banks require justification of higher income or the CPF monies of a co-purchaser is required for down payment or monthly instalment payment), then consider purchasing your property as tenants in common in the proportion of 99% to 1%. In future, if the 1% owner wishes to buy a second/subsequent property, the decoupling cost for the 1% would be insignificant. Meanwhile, being the 1% owner does not restrict the amount of the 1% owner’s CPF funds that can be used for the purchase. This means that the 1% owner can use his CPF funds in a sum exceeding his 1% share in the property.

Characterist LLC’s Adrian Wee, Dominic Chan, Noel Oehlers, Daniel Ng, and Nicole Chee, are representing the Ngee Ann Kongsi in their application for an urgent Court order for the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan to deliver up vacant possession of the premises it occupies in the Teochew Building at 97 Tank Road, in order that redevelopment works for the Teochew Building may commence.

The Ngee Ann Kongsi had planned for the redevelopment works for the Teochew Building to start on 1 July 2018. At the end of June 2017, the Ngee Ann Kongsi had served notice on the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan for it to move out by the initial deadline of 30 June 2018. What followed were negotiations between the parties on the arrangements in respect of the moving out. However, despite protracted negotiations, both parties could not reach a consensus on such arrangements. In the light of the negotiations, the redevelopment works were also postponed twice, and is currently due to commence on 2 January 2019 (with the handing over of the Teochew Building to the main contractors to take place on 17 December 2018).

However, as still no consensus could be reached between the parties, and with the deadline for the handing over and commencement of the redevelopment works drawing near, the Ngee Ann Kongsi had to take out an urgent application to the Supreme Court of Singapore for the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan to deliver up vacant possession of its premises to the Ngee Ann Kongsi.

The complete online version of the article may be found at the following link: https://www.zaobao.com.sg/znews/singapore/story20181208-914036

Persons who act as nominees in Voluntary Arrangements have a duty to act in utmost good faith. Where the nominee’s conduct of the creditors’ meeting is in bad faith, such that the nominee’s conduct is deficient, leading to a material irregularity at or in relation to the creditors meeting, the nominee may, in appropriate cases, be personally liable to pay the legal costs of affected creditors.

Individuals facing imminent bankruptcy proceedings have the option of attempting a Voluntary Arrangement (VA) pursuant to Section 45 of the Bankruptcy Act. The VA entails the debtor making a proposal to his/her creditors, usually involving a deferral of payment and a reduction in the total amount owed. The proposal is then voted on by creditors. If the proposal is approved by a special majority of creditors, the VA is then binding on all creditors. In this respect, the VA is not dissimilar to the Scheme of Arrangement regime for companies.

Key to the VA scheme is the role of the nominee. The nominee is a qualified insolvency practitioner who is appointed to oversee the VA process and to adjudicate creditors’ claims for the purpose of voting. However, as the nominee is usually proposed and paid for by the debtor (who has, in turn, already satisfied him/herself of the nominee’s sympathies to the cause), obvious questions often arise as to the impartiality of the nominee.

In the case of Balbeer Singh Mangat and Sirjit Gill,[1], both Debtors applied for a joint voluntary arrangement (JVA). The Nominee appointed is a Senior Partner in the largest audit, tax and consulting firm outside the Big Four in Singapore. Having supported the Debtors’ JVA proposal, the Nominee convened a creditors’ meeting.

At the creditors’ meeting, the Nominee made 2 key decisions:

- The votes of creditors whose claims were marked “objected to” were not to be counted for the purposes of voting; and

- The result of the creditors’ vote could not be determined until the court had ruled on the correctness of the Nominee’s decision to mark certain creditors’ votes “objected to”.

The effect of the Nominee’s decisions was to shift the task of adjudication of claims from the Nominee to the Court.

Several major creditors applied for a review of the Nominee’s decisions and conduct.

In determining that the proposal had not been passed at the creditors’ meeting, the Court made the following observations:

- The Nominee had acted improperly in marking the creditors’ votes “objected to”;

- It was clear from Rule 84(6) of the Bankruptcy Rules that any creditor whose claim was marked “objected to” should nonetheless be allowed to vote and such vote should be counted for the purposes of determining whether the proposal had passed unless it was subsequently declared invalid by the Court. In this respect, the Nominee had acted improperly in excluding votes marked “objected to” and was in breach of his duty and responsibility. The Nominee’s actions defied logic;

- In leaving the decision as to whether the proposal had been passed to the Court, the Nominee was trying to evade his responsibility by “fudging the issues and his decision”.

For the above reasons the Court held that there were material irregularities in the conduct of the creditors’ meeting. The Nominee was ordered to pay personally half of the costs of the creditors’ applications.

It should be noted that, in certain circumstances, nominees are protected from being made personally liable for costs. For example, Rule 84(10) of the Bankruptcy Rules provides that a nominee cannot be liable for costs even if his/her decision as to whether a creditor’s claim should be accepted or rejected for the purposes of entitlement to vote at a creditors’ meeting is wrong and reversed on appeal.

However, the protection under Rule 84(10) does not extend to conduct of the nominee which results in material irregularity in respect of the creditors’ meeting itself. This includes conduct which is in bad faith and/or a breach of the nominee’s duties in relation to the meeting.