Creditors might generally be reluctant to embark on litigation in order to recover debts owing from an insolvent company or bankrupt – even if it involves a complex and highly disputed claim. This is understandable since the prospects of success and eventual recovery may be limited. To save time and costs, they would much rather file a proof of debt and have it adjudicated by the liquidator / private trustee in bankruptcy (PTIB).

The case of Yit Chee Wah (as private trustee of the estate of Chan Siew Lee Jannie, a bankrupt) v Fulcrum Distressed Partners Ltd [2026] SGHC(A) 1 provides guidance on when the proof of debt regime is unsuitable for resolving such claims, and what to do next.

Background

This case concerned the admission/rejection of certain parts of a proof of debt filed against the bankruptcy estate of Ms Jannie Chan Siew Lee.

The liquidators of Timor Global Pte Ltd (“TGPL”) filed a proof of debt against Ms Chan’s bankruptcy estate for four sums, including the TL Sum and Finished Goods Sum which were the subject of the appeal.

TGPL was in the business of agricultural trading, such as coffee beans. It was involved in a joint venture with a Timor Leste company, Timor Global (TL) Pte Ltd (“TL”) and Intraco Trading Pte Ltd (“Intraco”) for the processing and trading of coffee beans, with the profits to be shared between TGPL and Intraco.

- Under the terms of the JV agreement:

(a) TGPL would place orders for processed coffee beans from Intraco, and Intraco would in turn order an equivalent amount from TL. Intraco would make an advance payment to TL to enable it to purchase raw materials from third parties, and then process them into coffee beans.

(b) Intraco would on-sell the coffee beans to TGPL at cost, who would then market and sell them to third party buyers.

(c) TGPL and Intraco split the profits according to a formula.

- At the material time, Ms Chan was one of the directors of TGPL, and a shareholder in TL.

The TL Sum was S$15,766,460 and referred to receivables allegedly owed by TL to TGPL as at 31 December 2014.

The Finished Goods Sum referred to a sum of US$2,301,767.43 which allegedly represented sales proceeds from coffee beans sold by TGPL in 2008 which were allegedly paid directly by TGPL’s customers to TL between 19 June 2008 and 14 November 2009.

The basis of the claim for both sums was that Ms Chan had breached her fiduciary duties as a director of TGPL. This arose because TGPL’s liquidators found discrepancies in the records of TGPL as to the amounts due from TL.

- TGPL subsequently assigned its claims against Ms Chan to Fulcrum Distressed Partners Ltd (“FDPL”).

Ms Chan’s private trustee in bankruptcy, Mr Yit Chee Wah, adjudicated the proof of debt and rejected the claims for both the TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum.

(a) The TL Sum was rejected because (i) the documents did not provide satisfactory evidence that Ms Chan breached her custodial fiduciary duties to TGPL, and (ii) the claim was time-barred.

(b) The Finished Goods Sum was rejected because (i) there was insufficient evidence that Ms Chan instructed the customers to make these payments to TL or knew about them, and (ii) there was no evidence that Ms Chan directly benefitted from TL’s receipt of the Finished Goods Sum.

- FDPL appealed against Mr Yit’s adjudication decision to the Court, which found that:

(a) The TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum were capable of being provable debts, if established by the evidence.

(b) The TL Sum should be admitted in full, and was not time-barred.

(c) The Finished Goods Sum should be admitted.

- Mr Yit appealed against the lower Court’s decision, to the Appellate Division of the High Court.

Legal Framework

The proof of debt regime is not meant to be used to adjudicate matters involving controversial disputes of fact. There is a policy of efficiency underlying this regime. When faced with a proof of debt that involves disputes of fact that cannot be easily resolved on documentary evidence, the liquidator/PTIB is entitled to reject it.

When serious allegations are made (such as misfeasance and fraud), this suggests that cross-examination of witnesses is necessary and it is inappropriate for the disputed claim to be resolved under the proof of debt regime. This is unless the serious allegation is clearly made out on the documentary evidence, or there is no serious dispute about the existence of such misconduct.

The proper recourse for a liquidator/PTIB when faced with factually complex disputes is to either (a) reject the proof of debt with reasons or (b) seek directions from the Court on the manner in which it should be resolved (pursuant to s 145(3) of the IRDA for corporate insolvency cases, or s 43(2) of the IRDA / s 40(2) of the BA for personal insolvency cases).

In the latter case, the Court may find that a full trial, or limited cross-examination of key witnesses, is necessary for the resolution of the issues. The paramount consideration is whether oral examination of witnesses and/or discovery is necessary for fairly disposing of the particular issue. This depends on the facts of each case, and the court will not order oral examination of witnesses where such an order would be unnecessary or oppressive. The court may also consider whether there are gaps in the documentary / affidavit evidence.

- These principles apply with equal force in both corporate and personal insolvency proceedings.

The Court’s Holding

The Appellate Division allowed the appeal and set aside the lower Court’s orders for Mr Yit to admit the TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum. Instead, the Appellate Division ordered a full trial on the claims by FDPL against Ms Chan’s bankruptcy estate.

This was because the documentary and affidavit evidence did not clearly establish whether Ms Chan was in breach of her duty to act honestly and bona fide in TGPL’s interests in respect of the TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum. Further, the material disputes of fact in relation to FDPL’s claims render them unsuitable to be decided without a trial. FDPL ought to be given an opportunity to properly prove its claims through the trial process.

- The five issues to be determined in respect of FDPL’s claims were:

(a) Whether the TL Sum represents a genuine debt owed by TL to TGPL, in particular, whether they were made pursuant to the JV agreement, or loans from TGPL to TL;

(b) What is the quantum of the TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum;

(c) Whether Ms Chan authorised or caused TGPL to make payments comprising the TL Sum, and gave instructions to TGPL’s customers to pay the Finished Goods Sum to TL;

(d) Whether Ms Chan breached her fiduciary duties by failing to cause TGPL to recover the TL Sum and the Finished Goods Sum from TL (assuming they were genuine debts owed by TL to TGPL); and

(e) If the answer to the third or fourth issues were in the affirmative, whether FDPL’s claims against Ms Chan are time-barred.

Ordering a full trial was appropriate on the facts of the case. Ordering cross-examination of the deponents of the affidavits would not be sufficient. The points in contention had not been clearly defined, there were numerous gaps in the affidavit and documentary evidence, and certain individuals with knowledge of the material facts would have to be ordered to give evidence and examined in court.

- To give some examples:

(a) On the first issue, it appeared that TGPL had made payments of certain sums within the TL Sum to TL pursuant to the JV agreement (i.e., for TL to purchase raw materials and process them into coffee beans). If so, there could be no issue of any breach of fiduciary duty by Ms Chan. However the TL Sum also appeared as a receivable in the management accounts of TGPL, and there were significant unexplained variances between this and the company’s audited financials statements between 2005 and 2008. The directors/staff of TGPL who had handled these payments should give evidence on the reasons for these payments and might be able to shed light on the reasons why they were made to TGPL instead of TL, and why they were recorded as loans in TGPL’s books. Ms Chan had also made contradictory statements as to whether these were loans due from TL to TGPL, and the extent of her involvement in TGPL. These are clear material disputes of fact which ought to be resolved by way of cross-examination.

(b) On the third issue of whether Ms Chan authorised TGPL to grant the TL Sum and instructed customers to transfer the Finished Goods Sum to TL, the only evidence before the Court was an observation by TGPL’s liquidators that the books and records of TGPL were under the management and control of Ms Chan until its winding up, and that Ms Chan had signed off on TGPL’s financial statements and was an authorised bank signatory. There was however no evidence as to Ms Chan’s knowledge at the time the payments were made. This was also contradicted by Ms Chan’s evidence in her sworn statements on the extent of her involvement in TGPL. She ought to be cross-examined on these apparent contradictions.

(c) On the fourth issue, the legal test of whether a director had breached her duty to act bona fide and honestly is part-subjective and part-objective. For example, where she comes to know about a transaction which is against the company’s interest, believes that it is so, but does nothing to try to prevent the transaction or reverse it. The available evidence was insufficient to show that Ms Chan failed to cause TGPL to pursue the receivables, and the reasons for her acts and omissions. Causation was also an issue i.e., whether TGPL could have recovered the full sum even if it had pursued repayment from TL. Further evidence from Ms Chan, TL’s director and possibly staff from TL who handled their finances would be needed to determine this question.

Key Takeaways

The practical reality is that parties generally try to avoid litigation when it comes to recovering debts in an insolvency scenario, since it may be cheaper and more expedient to file and adjudicate a proof of debt. This judgement is a timely reminder that the regime’s policy of efficiency is a double-edged sword, which renders it unsuitable for resolving complex factual disputes. This is especially so where the claim entails serious allegations of misconduct that cannot be proved on documentary evidence alone.

Ultimately, both creditors and insolvency practitioners have to make a judgement call about what is the best way to resolve such claims. Appealing the adjudication decision may be low-cost in the short term, but could end up increasing costs in the long run, if the Court directs parties to head to a full trial. It may in some cases turn out to be more cost effective to refer the matter to Court and obtain an order for cross-examination of certain key witnesses, once the main issues have been distilled. As part of the recovery/adjudication strategy, the parties may consider whether incorporating alternative dispute resolution (such as mediation) could yield better outcomes.

If you would like to discuss the implications of this decision on your insolvency matters, we would be happy to advise.

In WPA v WPB & Ors [2025] SGHCF 24 (“GD”), the General Division of the High Court (Family Division) allowed the Plaintiff’s claim, to remove the 2nd Defendant as an executor of the estate (estimated between A$128m and A$150m) of their late mother (“Y”), due to inter alia conflicts of interest and for not performing his duties as an executor with due diligence and speed.

The Plaintiff was also substituted in as an administrator, despite the strenuous objections of most of the Defendants.

Characterist LLC’s Dominic Chan and Noel Oehlers successfully acted for the Plaintiff in this case.

Facts and Issues

The Plaintiff commenced the Suit in 2021, to remove the 1st and 2nd Defendants as the executrix and executor, respectively, of Y’s estate.

Section 32 of the Probate and Administration Act 1934 (2020 Rev Ed) provides that any probate may be revoked or amended for any sufficient cause. This requires the court to consider whether there has been an undue or improper administration of the estate in total disregard of the interests of the beneficiaries (Jigarlal Kantilal Doshi v Damayanti Kantilal Doshi (executrix of the estate of Kantilal Prabhulal Doshi, deceased) and another [2000] 3 SLR(R) 290 at [12]). Where, for instance, the executors are found to be tardy in distributing the assets of the estate or acting in conflict with the beneficiaries’ interests, the court may revoke a probate (UVH and another v UVJ and others [2020] 3 SLR 1329 at [73]-[74]). See [6] of the GD.

Whether the 1st and 2nd Defendants should be removed depended on secondary questions — whether they had acted in conflict of interests or, alternatively, they had been dilatory in their duties as executors to the extent that warrant their removal (see [7] of the GD).

It was one of the grounds of the Plaintiff’s claim that the 2nd Defendant was in a position of conflict of interests between his duties as an executor of Y’s estate and the negotiation and distributing of assets from the estate to himself (and the 3rd Defendant). The second ground of the Plaintiff’s claim was that the executors had not performed their duties with due diligence and speed (see [21] of GD).

Court’s Findings

The Court was satisfied that the Plaintiff had proven both claims (see [22] of GD).

Amongst other findings:

- It was precisely that the 2nd Defendant was representing himself, seeking payments out of the estate that affected his position as an executor. The act created a conflict of interests whether or not the Australian administrator of Y’s estate may have approved the payments (see [20] of the GD);

- There was no excuse in not administering the estate diligently (see [25] of the GD);

- The Court granted the Plaintiff Letters of Administration with Will Annexed in respect of the estate of Y, in substitution of the 2nd Defendant (see [28] of the GD) – this was despite strenuous objections by the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Defendants who alleged that the Plaintiff was not suitable to be the administrator (see [27] of the GD);

- The Court declined to substitute the 3rd and 4th Defendants in as administrators, for various reasons (see [26] of the GD).

The Plaintiff succeeded in proving both claims, i.e. conflict of interests (as against the 2nd Defendant only) and the executors not performing their duties as executors with due diligence and speed (save that the 1st Defendant was retained as an executrix, for other reasons (see [23] of the GD)).

Commentary

It is very important for an executor of an estate: (1) not to place himself or herself in a position of conflict of interests; and (2) to perform his or her duties with due diligence and speed.

Not abiding by such duties are potential grounds for possibly being removed and/or replaced by others.

In addition, even if an executor is removed, the Court would still have to go through the important exercise (which can give rise to highly contentious allegations between the parties) of determining who is suitable (or unsuitable) to be the replacement, after giving appropriate weight to and balancing all relevant factors.

We are delighted to announce that Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2025 has once again named Characterist LLC as a Recommended Firm in Commercial and Transactions and Construction, and this year, in Family and Matrimonial as well.

We are also happy to congratulate Daniel Goh and Dominic Chan for continuing to be recognised as Litigation Stars for the second year running.

We would like to thank our clients and our Characterist team for making these achievements happen!

Find out more here.

Characterist is delighted to announce that Francis Wong (previously Senior Associate Director) and Johnston Lee (previously Associate Director) have been promoted to Director and Senior Associate Director respectively.

Francis heads the firm’s Construction practice and also handles Commercial Disputes, while Johnston has varied practice in Family law, Personal Injury / Negligence, Estate planning, Probate and Property Law.

A tragic loss of a young life. Our Daniel Goh acts for the family.

“During the inquiry, Mr Daniel Goh, a lawyer representing the family, asked why SI Tan said Ms Tan had “dashed” across the road.

Said Mr Goh: “She took perhaps one step, a very sad step, but it’s not tantamount to dashing across (the road).”

SI Tan replied that from TP’s investigations, Ms Tan’s step onto the road felt like a running motion.

…

Mr Goh also asked about the van’s speed and noted the speed limit of the area was 50kmh.SI Tan said he did not know, but could put in a request for the authorities to analyse the van’s speed. He added he was unable to tell via the video footage if the van was travelling below the area’s speed limit.”

Read the full Straits Times article here.

Like the proverbial pink elephant in the room, one assumes that a ship is immediately and obviously identifiable. However, locally, and internationally, the definition of what is a ship has proved illusory, the criterion being “at sea” as it were.

Among the more unusual cases which have come up for determination would rank the following:

- Houseboats & floatels i.e. floating motels (The Environment Agency v Gibbs and another [2016] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 69, Addison v. Denholm Ship Management (UK) Ltd. [1997] I.C.R. 770);

- Flying boats (Polpen Shipping Co.v Commercial Union Assurance Co., Ltd (1942) 74 LI LR 157); and

- A remotely operated underwater vehicle (Guardian Offshore AU Pty Ltd v Saab Seaeye Leopard 1702 Remotely Operated Vehicle Lately on Board the Ship “Offshore Guardian” and another [2020] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 201).

To add to the list of curious cases, in the landmark case of Vallianz Shipbuilding & Engineering Pte Ltd v Owner of the vessel “ECO SPARK” [2023] SGHC 353 (“EcoSpark”), the Singapore Court had occasion to consider whether or not a floating fish farm (a modern day kelong in local parlance), was a ship for purposes of the HCAJA. In so doing, the Singapore Court has attempted to put forward a more comprehensive rubric by which to determine what is a ship, and this article wades into these murky waters by way of a case review.

The High Court (Admiralty Jurisdiction) Act 1961 (2020 Rev Ed) (“HCAJA”) is the legislation that sets out the ambit of the local Courts’ admiralty jurisdiction. Section 2 of the HCAJA defines “ship” as simply “any description of vessel used in navigation”. However, a neat definition of a “ship” or “vessel” has proved elusive. The High Court in EcoSpark has held (at [69]) that of necessity, the inquiry as to what constitutes a “ship” must be multi-factorial.

Practically speaking, the more ship-like characteristics one could tick off, the more likely the vessel is a “ship” and vice versa. However, the absence of certain characteristics does not immediately mean that the vessel is not a “ship”.

Relevant physical characteristics

Insofar as physical characteristics of a vessel were concerned, the “ability to self-propel, being possessed of a keel or a steering mechanism such a rudder, having a crew to man the ship, navigation lights, and ballast tanks” are usual physical characteristics (at [73]) and a vessel having all or most of these characteristics is more like than not to be a “ship”.

Design and capability of being used in navigation

At its very essence however, the Court noted that whether a vessel was “designed and capable of being used in navigation” was a weighty consideration in determining whether or not a vessel was a “ship” within the meaning of the HCAJA.

In that regard, a vessel must be designed to be capable of movement from one place to another on the water, but, need not be currently used to move from one place to another on water. Inasmuch as a car parked in a parking lot remains a car, a vessel not currently traversing the water (but capable of it) remains a vessel.

In addition, the Court declined to follow the line of authorities which hold that the vessel’s primary work should be executed while in navigation, and adopted instead the reasoning in the English Court of Appeal in Perks v Clark (Inspector of Taxes) [2001] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 431, that navigation can be incidental to another function such as dredging or providing accommodation.

Class and flag

Further to the above, the classification of the vessel, and registration and flag of the vessel in question has also been flagged out an important indication as to whether the vessel is a “ship” and/or “used in navigation”.

Conclusion

In this case, notwithstanding that the vessel the ECO SPARK, lacked many of the usual physical characteristics of a ship e.g. no engines, no crew, no navigational equipment, the Court noted that the vessel, being a converted dumb barge, was designed for and remained capable of being in navigation. The fact that she had special structures installed on top of the barge structure did not render her no longer navigable.

While the vessel was spudded down into the seabed and does not move on a daily basis, she is capable of being moved and remains capable of navigation. In addition, the fact that she had been towed from Batam to Singapore immediately prior to her use as a floating fish farm, and her capability of being classed (notwithstanding that her owners had not maintained her class status), pointed to her being a ship for the purposes of section 2 of the HCAJA.

In conclusion, this judgment is a timely and illuminative one and provides a greater degree of certainty and clarity as to when the admiralty jurisdiction of the Singapore courts is to be invoked.

On Friday, 5 July 2024, Characterist shared a merry evening of drinks and canapes, laughter and conversations with our clients during Characterist Casual, our firm’s client thanksgiving event.

We would like to take the opportunity to express our heartfelt gratitude to our clients and all who attended.

Some of the more common offences a driver may face under the Road Traffic Act 1961 (the “RTA”) include “Reckless or dangerous driving” under Section 64 of the RTA (“Reckless Driving”) and “Driving without due care or reasonable consideration” under Section 65 of the RTA (“Careless Driving”). This article explores what these offences mean and the judicial approach to dealing with such offences, as well as some of the possible outcomes a person may face when charged with such offences.

Defining the Offences

First, when faced with a possible RTA offence, it is important to understand whether one’s conduct amounts to “carelessness” as opposed to “recklessness” which is more severe. These terms are not defined in the RTA but have developed over case law.

Broadly, recklessness involves the offender’s recognition of a risk (such as beating a red light, or driving under the influence) but ignoring that risk. Recklessness can also be made out where a risk is obvious but the driver unreasonably failed to consider it. Carelessness on the other hand is typically made out when a driver’s actions fall below what is reasonably expected of a competent driver.

Second, there are 4 degrees of harm involved in such offences: death, grievous hurt, hurt, and non-injury scenarios or property-damage-only cases.

“Hurt” is elevated to “grievous hurt” when among other things, a victim has suffered permanent blindness or hearing loss in either eye, amputation, permanent disfiguration of the head or face, permanent incapacity to a body part, a fracture or dislocation of a bone (including the cartilage in the nose) or has been placed on medical leave for 20 days or more. The full list may be found at Section 320 of the Penal Code 1871.

The dividing line between what is reckless and what is careless is not always clear but this line must be drawn as the fines and / or imprisonment terms imposed can differ significantly between Reckless and Careless Driving.

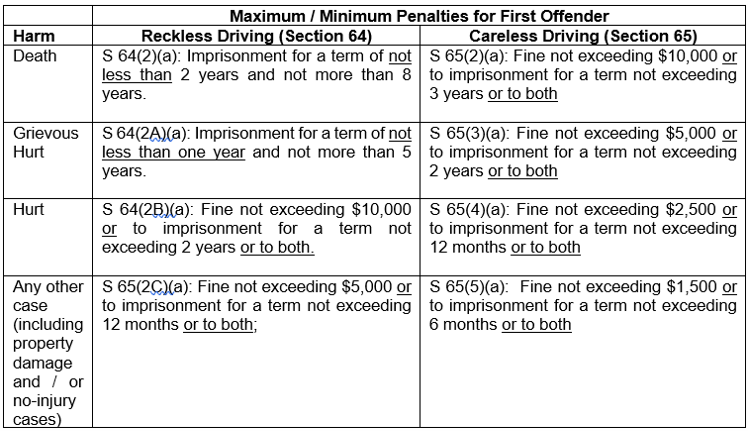

The table below lays out the minimum / maximum fines / terms of imprisonment for the offences of Reckless and Careless driving (not including any period of disqualification from driving which may be imposed). It may be observed that for certain levels of harm, the offence of Reckless Driving can carry mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment.

The Courts’ Approach to Sentencing

It is not possible here to lay out all of the possible considerations a sentencing Court may take into account. At this time of writing, the judicial approach to sentencing for Careless and Reckless driving appears to still be undergoing development.

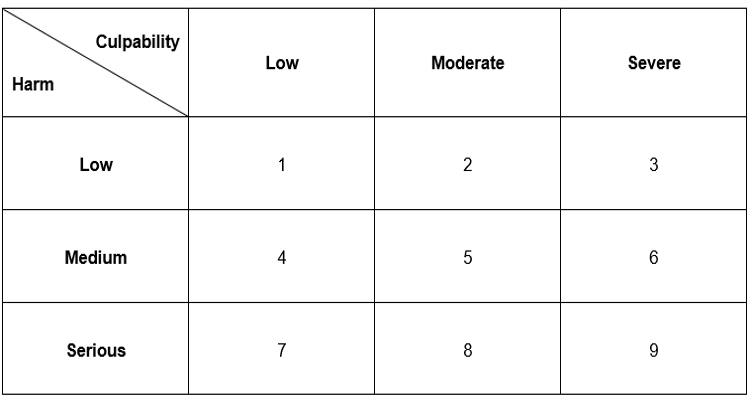

Generally, the Courts tend to begin by considering the level of Harm caused, and the Culpability of the Offender to determine the starting sentence. A crucial consideration is whether the case warrants a jail term or whether a fine is sufficient where there is no mandatory imprisonment. This is called the “custodial threshold” which is often a foremost consideration to potential offenders.

There is case law to suggest that at least for the offence of Reckless Driving, the custodial threshold is not usually reached in cases where the level of Culpability lies between low to moderate and the degree of Harm is between low to medium (i.e. boxes 1, 2, and 4 but not 5 in the table below), if there are no aggravating factors. However, each case will be determined on their own facts.

The level of Harm and Culpability are assessed on a case-by-case basis. For Culpability, conduct which tends to fall within the low to moderate range includes behaviour such as beating a red light. If there are multiple breaches of safe driving practices, it may be expected that Culpability will be higher, and where very dangerous conduct such as driving under the influence or road racing is concerned, these factors may push Culpability into the severe range.

For Harm, naturally if death is caused, it will fall within the serious range. Where victims have suffered multiple fractures or a degree of severe permanent injury, Courts have also tended to assess Harm at between the moderate to serious ranges. On the other hand, where there are no fractures or severe injuries, Harm tends to fall at the low end. It should be noted that potential harm to other road users is also accounted for in this analysis.

After the Court has decided its starting sentence, including whether or not a sentence of imprisonment is warranted, then the Court will adjust the sentence based on other relevant aggravating and mitigating factors. Some examples of other aggravating factors include whether the offender has a record of past driving offences.

In conclusion, understanding the law behind the offences of Reckless and Careless Driving can be a complicated and stressful procedure. The law is also continually developing in this regard, and the best advice one should walk away with is to drive safely and with proper consideration for the rules and for other road users.

We are proud to congratulate our Directors Daniel Goh and Dominic Chan for being recognised by Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2024 as Litigation Stars in their respective fields of Insurance and Commercial and Transactions.

Find out more at the following links:

https://benchmarklitigation.com/Lawyer/Daniel-Goh/Profile/146409#profile

https://benchmarklitigation.com/Lawyer/Dominic-Chan/Profile/134547#profile

We are delighted to announce that Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2024 has named Characterist LLC as a Recommended Firm in Commercial and Transactions and Construction and a Notable Firm in Family and Matrimonial. We would like to say a big thank you to our clients and our Characterist team for making these achievements happen!

Learn more at the following links:

(1) Our Benchmark Litigation profile page

(2) Our Benchmark Litigation rankings page

(3) Benchmark Litigation’s analysis page of Characterist