We are delighted to announce that Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2025 has once again named Characterist LLC as a Recommended Firm in Commercial and Transactions and Construction, and this year, in Family and Matrimonial as well.

We are also happy to congratulate Daniel Goh and Dominic Chan for continuing to be recognised as Litigation Stars for the second year running.

We would like to thank our clients and our Characterist team for making these achievements happen!

Find out more here.

Characterist is delighted to announce that Francis Wong (previously Senior Associate Director) and Johnston Lee (previously Associate Director) have been promoted to Director and Senior Associate Director respectively.

Francis heads the firm’s Construction practice and also handles Commercial Disputes, while Johnston has varied practice in Family law, Personal Injury / Negligence, Estate planning, Probate and Property Law.

A tragic loss of a young life. Our Daniel Goh acts for the family.

“During the inquiry, Mr Daniel Goh, a lawyer representing the family, asked why SI Tan said Ms Tan had “dashed” across the road.

Said Mr Goh: “She took perhaps one step, a very sad step, but it’s not tantamount to dashing across (the road).”

SI Tan replied that from TP’s investigations, Ms Tan’s step onto the road felt like a running motion.

…

Mr Goh also asked about the van’s speed and noted the speed limit of the area was 50kmh.SI Tan said he did not know, but could put in a request for the authorities to analyse the van’s speed. He added he was unable to tell via the video footage if the van was travelling below the area’s speed limit.”

Read the full Straits Times article here.

Like the proverbial pink elephant in the room, one assumes that a ship is immediately and obviously identifiable. However, locally, and internationally, the definition of what is a ship has proved illusory, the criterion being “at sea” as it were.

Among the more unusual cases which have come up for determination would rank the following:

- Houseboats & floatels i.e. floating motels (The Environment Agency v Gibbs and another [2016] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 69, Addison v. Denholm Ship Management (UK) Ltd. [1997] I.C.R. 770);

- Flying boats (Polpen Shipping Co.v Commercial Union Assurance Co., Ltd (1942) 74 LI LR 157); and

- A remotely operated underwater vehicle (Guardian Offshore AU Pty Ltd v Saab Seaeye Leopard 1702 Remotely Operated Vehicle Lately on Board the Ship “Offshore Guardian” and another [2020] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 201).

To add to the list of curious cases, in the landmark case of Vallianz Shipbuilding & Engineering Pte Ltd v Owner of the vessel “ECO SPARK” [2023] SGHC 353 (“EcoSpark”), the Singapore Court had occasion to consider whether or not a floating fish farm (a modern day kelong in local parlance), was a ship for purposes of the HCAJA. In so doing, the Singapore Court has attempted to put forward a more comprehensive rubric by which to determine what is a ship, and this article wades into these murky waters by way of a case review.

The High Court (Admiralty Jurisdiction) Act 1961 (2020 Rev Ed) (“HCAJA”) is the legislation that sets out the ambit of the local Courts’ admiralty jurisdiction. Section 2 of the HCAJA defines “ship” as simply “any description of vessel used in navigation”. However, a neat definition of a “ship” or “vessel” has proved elusive. The High Court in EcoSpark has held (at [69]) that of necessity, the inquiry as to what constitutes a “ship” must be multi-factorial.

Practically speaking, the more ship-like characteristics one could tick off, the more likely the vessel is a “ship” and vice versa. However, the absence of certain characteristics does not immediately mean that the vessel is not a “ship”.

Relevant physical characteristics

Insofar as physical characteristics of a vessel were concerned, the “ability to self-propel, being possessed of a keel or a steering mechanism such a rudder, having a crew to man the ship, navigation lights, and ballast tanks” are usual physical characteristics (at [73]) and a vessel having all or most of these characteristics is more like than not to be a “ship”.

Design and capability of being used in navigation

At its very essence however, the Court noted that whether a vessel was “designed and capable of being used in navigation” was a weighty consideration in determining whether or not a vessel was a “ship” within the meaning of the HCAJA.

In that regard, a vessel must be designed to be capable of movement from one place to another on the water, but, need not be currently used to move from one place to another on water. Inasmuch as a car parked in a parking lot remains a car, a vessel not currently traversing the water (but capable of it) remains a vessel.

In addition, the Court declined to follow the line of authorities which hold that the vessel’s primary work should be executed while in navigation, and adopted instead the reasoning in the English Court of Appeal in Perks v Clark (Inspector of Taxes) [2001] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 431, that navigation can be incidental to another function such as dredging or providing accommodation.

Class and flag

Further to the above, the classification of the vessel, and registration and flag of the vessel in question has also been flagged out an important indication as to whether the vessel is a “ship” and/or “used in navigation”.

Conclusion

In this case, notwithstanding that the vessel the ECO SPARK, lacked many of the usual physical characteristics of a ship e.g. no engines, no crew, no navigational equipment, the Court noted that the vessel, being a converted dumb barge, was designed for and remained capable of being in navigation. The fact that she had special structures installed on top of the barge structure did not render her no longer navigable.

While the vessel was spudded down into the seabed and does not move on a daily basis, she is capable of being moved and remains capable of navigation. In addition, the fact that she had been towed from Batam to Singapore immediately prior to her use as a floating fish farm, and her capability of being classed (notwithstanding that her owners had not maintained her class status), pointed to her being a ship for the purposes of section 2 of the HCAJA.

In conclusion, this judgment is a timely and illuminative one and provides a greater degree of certainty and clarity as to when the admiralty jurisdiction of the Singapore courts is to be invoked.

On Friday, 5 July 2024, Characterist shared a merry evening of drinks and canapes, laughter and conversations with our clients during Characterist Casual, our firm’s client thanksgiving event.

We would like to take the opportunity to express our heartfelt gratitude to our clients and all who attended.

Some of the more common offences a driver may face under the Road Traffic Act 1961 (the “RTA”) include “Reckless or dangerous driving” under Section 64 of the RTA (“Reckless Driving”) and “Driving without due care or reasonable consideration” under Section 65 of the RTA (“Careless Driving”). This article explores what these offences mean and the judicial approach to dealing with such offences, as well as some of the possible outcomes a person may face when charged with such offences.

Defining the Offences

First, when faced with a possible RTA offence, it is important to understand whether one’s conduct amounts to “carelessness” as opposed to “recklessness” which is more severe. These terms are not defined in the RTA but have developed over case law.

Broadly, recklessness involves the offender’s recognition of a risk (such as beating a red light, or driving under the influence) but ignoring that risk. Recklessness can also be made out where a risk is obvious but the driver unreasonably failed to consider it. Carelessness on the other hand is typically made out when a driver’s actions fall below what is reasonably expected of a competent driver.

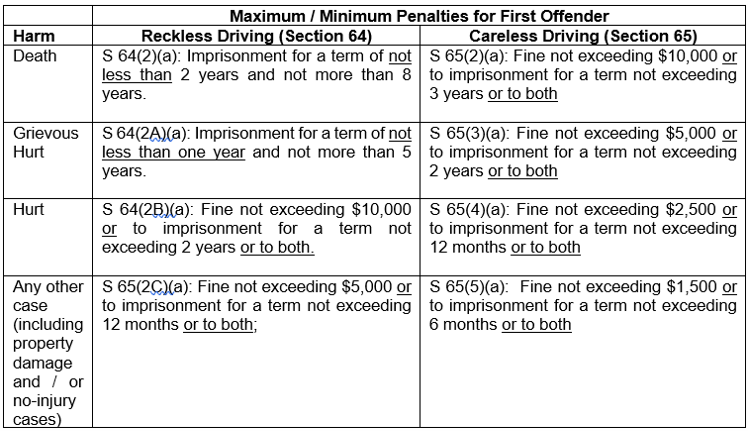

Second, there are 4 degrees of harm involved in such offences: death, grievous hurt, hurt, and non-injury scenarios or property-damage-only cases.

“Hurt” is elevated to “grievous hurt” when among other things, a victim has suffered permanent blindness or hearing loss in either eye, amputation, permanent disfiguration of the head or face, permanent incapacity to a body part, a fracture or dislocation of a bone (including the cartilage in the nose) or has been placed on medical leave for 20 days or more. The full list may be found at Section 320 of the Penal Code 1871.

The dividing line between what is reckless and what is careless is not always clear but this line must be drawn as the fines and / or imprisonment terms imposed can differ significantly between Reckless and Careless Driving.

The table below lays out the minimum / maximum fines / terms of imprisonment for the offences of Reckless and Careless driving (not including any period of disqualification from driving which may be imposed). It may be observed that for certain levels of harm, the offence of Reckless Driving can carry mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment.

The Courts’ Approach to Sentencing

It is not possible here to lay out all of the possible considerations a sentencing Court may take into account. At this time of writing, the judicial approach to sentencing for Careless and Reckless driving appears to still be undergoing development.

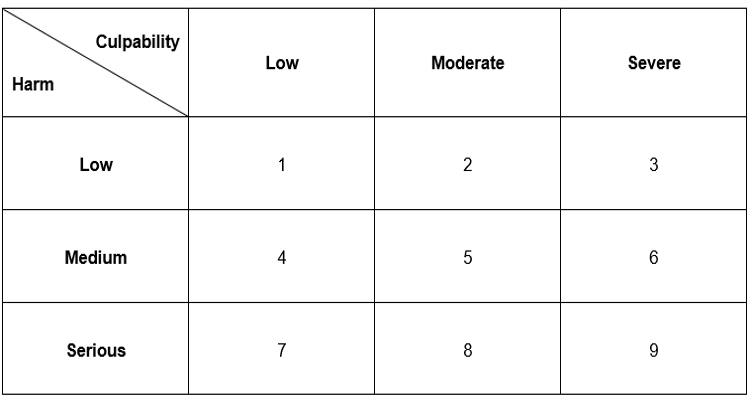

Generally, the Courts tend to begin by considering the level of Harm caused, and the Culpability of the Offender to determine the starting sentence. A crucial consideration is whether the case warrants a jail term or whether a fine is sufficient where there is no mandatory imprisonment. This is called the “custodial threshold” which is often a foremost consideration to potential offenders.

There is case law to suggest that at least for the offence of Reckless Driving, the custodial threshold is not usually reached in cases where the level of Culpability lies between low to moderate and the degree of Harm is between low to medium (i.e. boxes 1, 2, and 4 but not 5 in the table below), if there are no aggravating factors. However, each case will be determined on their own facts.

The level of Harm and Culpability are assessed on a case-by-case basis. For Culpability, conduct which tends to fall within the low to moderate range includes behaviour such as beating a red light. If there are multiple breaches of safe driving practices, it may be expected that Culpability will be higher, and where very dangerous conduct such as driving under the influence or road racing is concerned, these factors may push Culpability into the severe range.

For Harm, naturally if death is caused, it will fall within the serious range. Where victims have suffered multiple fractures or a degree of severe permanent injury, Courts have also tended to assess Harm at between the moderate to serious ranges. On the other hand, where there are no fractures or severe injuries, Harm tends to fall at the low end. It should be noted that potential harm to other road users is also accounted for in this analysis.

After the Court has decided its starting sentence, including whether or not a sentence of imprisonment is warranted, then the Court will adjust the sentence based on other relevant aggravating and mitigating factors. Some examples of other aggravating factors include whether the offender has a record of past driving offences.

In conclusion, understanding the law behind the offences of Reckless and Careless Driving can be a complicated and stressful procedure. The law is also continually developing in this regard, and the best advice one should walk away with is to drive safely and with proper consideration for the rules and for other road users.

We are proud to congratulate our Directors Daniel Goh and Dominic Chan for being recognised by Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2024 as Litigation Stars in their respective fields of Insurance and Commercial and Transactions.

Find out more at the following links:

https://benchmarklitigation.com/Lawyer/Daniel-Goh/Profile/146409#profile

https://benchmarklitigation.com/Lawyer/Dominic-Chan/Profile/134547#profile

We are delighted to announce that Benchmark Litigation Asia-Pacific 2024 has named Characterist LLC as a Recommended Firm in Commercial and Transactions and Construction and a Notable Firm in Family and Matrimonial. We would like to say a big thank you to our clients and our Characterist team for making these achievements happen!

Learn more at the following links:

(1) Our Benchmark Litigation profile page

(2) Our Benchmark Litigation rankings page

(3) Benchmark Litigation’s analysis page of Characterist

In a CNA Explains article on drink driving laws in Singapore, CNA examined the offence of drink driving in Singapore and the various penalties and consequences that offenders may face.

CNA interviewed various lawyers on the position in law, including Characterist’s Daniel Goh Choon Wah and Mitchell Leon.

Commenting on the recent amendments to the Road Traffic Act (RTA) in 2019, Mitchell highlighted that “the maximum sentences [for drink driving] were essentially doubled with the 2019 amendments [to the RTA], with the minimum disqualification period also doubled from 12 months to two years.” He also noted that “[i]t is clear that the enhanced sentencing regime post-2019 was intended to create a strong deterrence to would-be drink drivers, as well as irresponsible or reckless drivers”.

From a motor vehicle insurance perspective, Daniel commented that “in most cases, the insurance contract stipulates that drink driving constitutes grounds for the repudiation of insurance liability…In particular, some insurance policies might provide that any amount of alcohol consumed is grounds for repudiation. In other words, the driver need not necessarily exceed the legal limit under the Act of 80mg of alcohol in 100ml of blood”.

Read the full CNA article here.

Characterist’s Daniel Goh Choon Wah represented an ex-lawyer, David Khong Siak Meng, who had been charged with one count of criminal breach of trust.

Khong had acted for a couple in a conveyancing transaction, where he had deposited the buyer’s cheque of $88,000, paid in exercise of the option to purchase, into his firm’s office account instead of the firm’s clients’ account (which is specifically used for holding clients’ monies). He then proceeded to withdraw the full sum of $88,000 within the same month to pay off personal expenses and debts.

On 15 August 2007, the day after the sale was scheduled to be completed, Khong met his client and confessed to misappropriating the monies due to “personal problems”. He repaid his client $20,000 and asked for more time to repay the remaining $68,000. His client gave him till 18 August 2007 to do so, failing which, his client would make a police report. Khong was unable to do so and fled to China. Khong was eventually deported to Singapore on 23 September 2022.

Characterist’s Daniel Goh Choon Wah sought leniency for Khong from the Court, stating that “He would not have been arrested and deported (if not) for his clear and deliberate act of surrendering with the knowledge that he would have to be deported to Singapore to face the music”, and that “[h]e has matured in the long time away from home and should be afforded the opportunity to turn over a new leaf.”

Khong was sentenced to 36 months of jail. For committing criminal breach of trust as a lawyer, he could have received a jail sentence of up to twenty years, and also be liable to be fined.

Read more at this Straits Times article.